While convalescing this week I took the time to watch some television. I stumbled upon the show Absentia—which I wouldn’t recommend for a few reasons including someone asking “coffee?” While holding the bottom of the glass coffee pot with a bare hand, and the amount of math that was constantly running through my head as I tried to make the timeline work.

One of the most perplexing un-true to life instances happened at least once in all three seasons when the central character, Emily, received life threatening wounds and then popped up after a quick emergency surgery and was soon parkouring across Boston after the convoluted web of bad guys. Mind you, the closest thing I have received to an abdominal stab wound was my emergency c-section, but everyone thought it was pretty impressive when I was hiking a week later—no martial arts involved.

This brings me to the topic whirling around my head last night with the cough medicine. When a character on the page/stage/screen is injured how do we keep things real? And how do we preserve the narrative tension that might otherwise be lost in the numerous physical therapy visits?

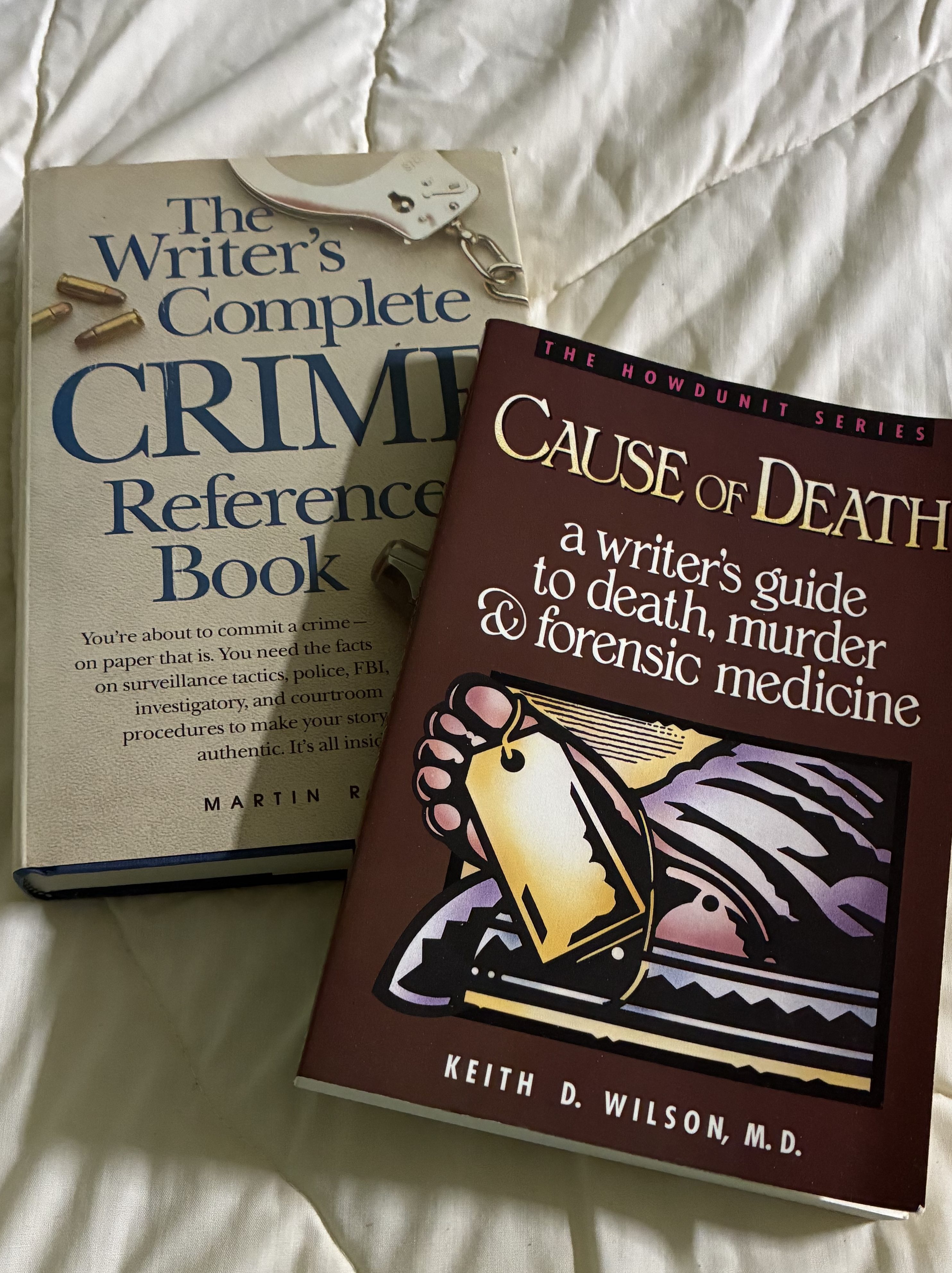

The first step to writing a realistic injury is doing your research. I have a handy book on my shelf called Cause of Death: a writers guide to death, murder & forensic medicine, by Keith D. Wilson, M.D. which, while a few years old still covers handy topics related to the title. There are plenty of similar resources out there, and of course the internet has a wealth of info. Most of the deaths I write are historical in nature, so Web M.D. has been handy to get symptom lists and progression. To be fair, I also have a resident pathologist in the house who is happy to share his thirty years of experience.

Violent injuries or deaths at the hands of another character with or without a weapon can add layers of complication. Caliber of bullets, serration on knives, variety of poison are all factors in how a character is going to be effected. The physical makeup of the victim and attackers, as well as their skills at defending themselves set the stage for the initial conflict.

Suzy, a 6’3 body builder who was a karate savant in her teens before dropping out to pursue her dream of competitive hair styling is attacked outside the national finals. She is in a lot less danger than her rival Cleo, who is 5’1 and at 70 is competing one last time before arthritis gets the best of her hands, who also happens to be outside in the ally. Both are sliced across the arm by the same attacker, using the same tool (a barber’s straight edge) before Suzy back kicks him into a dumpster.

Suzy is probably going to be fine. Her muscle bulk should have protected her arteries against the one lucky swipe that nicked her, and unless we find out she is a rampant steroid abuser, the stress will only amp her up for the competition. Cleo on the other hand has thinner skin and less muscle mass, and the shock of the attack may exacerbate pre-existing age related diagnoses. Cleo dies in the ally, but from blood loss? Or something else?

We never find out because Suzy is the protagonist and the narrative follows her. There should be physical and emotional/mental consequences to an injury. Maybe the full weight of the attack hits Suzy in the third round of competition as she is French braiding while also twirling flaming batons; the batons crash down, lighting a table of hairspray cans on fire and sending them ballistic missile style all over the amphitheater. Now on top of the emotional trauma of the attack, Suzy must also bear the weight of the sixty people who were injured due to her reckless baton twirling.

If this is a redemption story, Suzy comes back from the emotional and physical damage to become a better person. If this is a downward spiral story that shows the problematic subculture of competitive hair shows, then Suzy must suffer. Regardless, the injuries she sustains should feel like they could realistically cause the consequences that come after. If instead of a cut Suzy lost three fingers, she is not going to be out on the competition floor an hour later pulling off a flawless braid and rocking batons (and here is where I take a break to see if I can French braid with only seven fingers…and back).

So we have written a realistic injury, how do we keep up narrative tension when the character has to recuperate? One of two ways.

1. Skip time. In an action heavy story, we might jump forward a few months. This allows the character to heal off screen as well as get all moody and broody. It also works for characters recuperating from pregnancies or mental health crisis. You want to skip forward in time only if the recovery process does’t service your plot somehow.

2. If the recovery process DOES service your plot, use it. Injury is a great way to reset a character who is becoming too capable. There is also a layer of frustration and mental strain for a character who has to struggle with their new dependence on those around them, and vulnerability to the ills of the world.

Again, the important part of keeping the narrative tension is to choose carefully what you are showing your reader. When I say “service the plot” I am going back to the old formula: What does the protagonist want, How are they getting it, or not. The injury effects we see should be keeping the protagonist from their goal. Suzy may not be kept from her goal of hair stylist superstardom by the physical cut on her arm, but by the memories of the screams of the crowd as they trample each other to get away from the flaming cans of hairspray death.

In the case of Suzy, we don’t need to go to the doctor with her to see her stitches being removed, or which lotion she decides to try to keep the scar from getting gnarly—unless these things somehow tie into a B plot romance with the nurse practitioner who raises honeybees and makes lotion from the wax.

One of my very favorite authors, Jim Butcher of Dresden Files fame, handles injuries beautifully. While wizard Harry Dresden is able to heal some of his injuries, or make a potion to get through the pain, there are always consequences in the long run. Harry acknowledges those consequences and lives with them. Butcher uses both techniques of skipping time and incorporating the recovery process, as well as allowing the scars and aches to effect Harry long after the initial injuries. Each wound becomes not just a plot point, but a permanent modification of the character.

Writing Prompt: Jack stumbles on the stairs and his life is altered forever.

Leave a comment