Right. Calling Schrödinger’s Tension Band “spooky” is a stretch, but let’s be generous today.

The first time I introduced this concept was during the Craft Talk presentation component for graduating with my MFA. My advisor’s face went from confused, to intrigued, and finally settled on the lips pursed nodding in a mildly pleased way. Afterwards he told me to write up the idea and submit it somewhere, so here we are.

Erwin Schrödinger was a physicist who, while fascinating, isn’t a name bandied around traditional writing circles all that often. Most of us wouldn’t be able to pick him out of a textbook except that he came up with a thought experiment about a cat in a box. Schrödinger posited that if one were to put a cat in a box, they could not know if it were alive or dead and so therefore it was both until confirmed by observation. (The whole thing is about sub-atomic particles but no thank you, not today.)

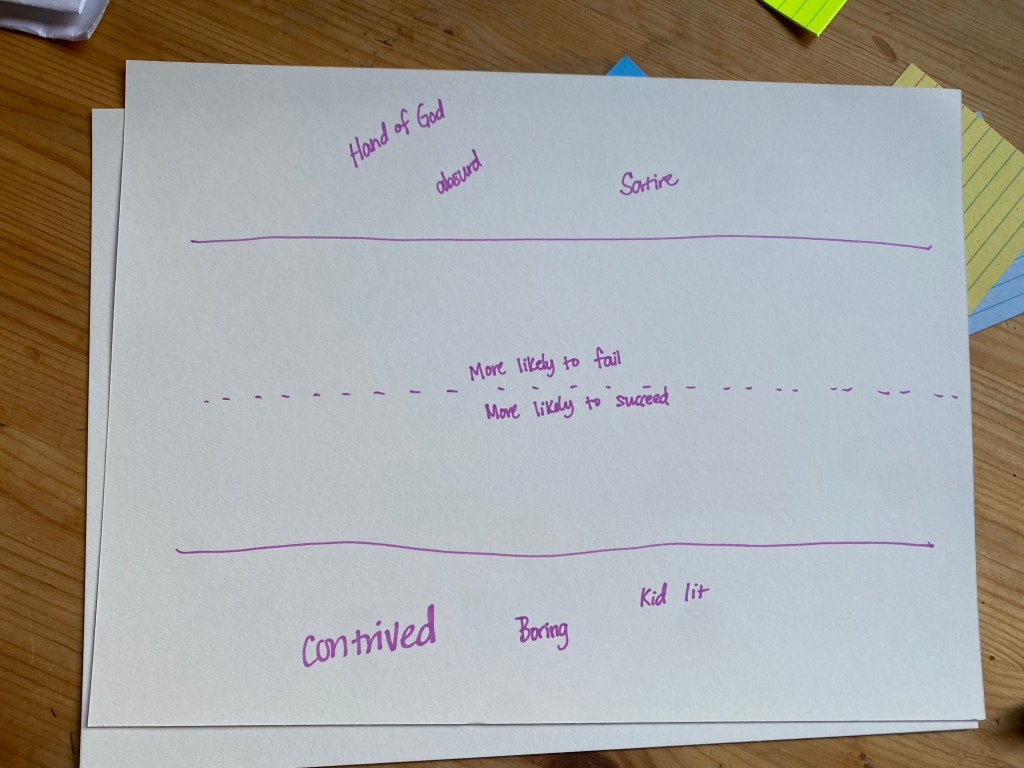

As writers we need not be so much concerned with Schrödinger’s Cat, but with what I call Schrödinger’s Tension Band. Imagine the picture above as a graph. When a character attempts a task, gets in a fight, or is working toward achieving their goals, in order to achieve narrative tension the reader must feel at once, as if the character might succeed or fail. The more likely the character is to fail, the higher the tension; the more likely the character is to succeed, the lower the tension. However, there are boundaries to this band. If a character goes out of bounds the story feels contrived or unrealistic.

So why is this important? Everything your character does sets expectations for the reader. Let’s say Joe the plumber is sent out on a call. Little does he know there is a zombie horde heading for town. If in the first scene, we see Joe competently fixing a toilet, flipping his wrench cheerfully (because he was a baton twirler back in high school), and turning a cartwheel as he returns to his shiny new van, when the upcoming fight scene arrives we will then expect to see some of those skills and resources utilized. We know Joe can wield a weapon and has a trusty steed.

On the other hand, if we are introduced to Joe as he struggles to turn off the water due to a wrist injury, stumbles over a throw rug, and the door handle falls off his rusty van? We are in for a very different fight.

If the first version of Joe were to lose to a single zombie wandering down the street, we would be stunned. If Joe version two won against a horde, we would be confused. Keeping in mind the tension band helps you to build conflicts that feel reasonable. This becomes more important as the story progresses.

After the initial success, or failure and escape by the skin of his teeth, Joe (and the reader) have a chance to recoup. It is great to level up a character between actions. They train, they add allies, get gear, go to therapy and work on their emotional flaws. This is important because the reader’s baseline in the tension band has reset. What felt like an eke out win last time is a sure thing now, so the danger (likeliness of failure) has to rise.

I’m going to side step here a moment. Any good dungeon master will tell you that the key to a good encounter is having well matched opponents. Build it too hard and you are going to end up with all the characters dead. Too easy and no one feels satisfied. The problem is that depending on your players, their gear, their feats, their spells, to make things feel well matched the baddies have to get bigger and bigger as well. It gets to the point that in order to write something with enough danger you are sacrificing story.

This happens on the page all the time. You have a character who is competent, intelligent, likable, and the external danger has to get so big that suddenly they are single handedly facing down an army just to get the reader’s heart pumping. What is an author to do?

-Character flaws. Joe the plumber? The really capable version? Give him a fear of death and black mold. Suddenly his wrench wielding skills aren’t going to matter if he can’t bear to get close enough to the moldy deadish for hand to hand combat. Flaws should get in the way of a character’s goals. Otherwise they are just quirks.

-Skills. Joe.2 has enough flaws, so he needs some secret, inherent talents that will help him succeed. Maybe he became a plumber in the first place after his career as a sommelier ended when he lost his sense of smell. The man can’t turn a wrench but nothing turns his tummy. He also has mad sword skills because opening wine bottles with a scimitar is a party trick—so I’ve heard.

Skills and flaws should show up in the exposition/introduction part of the plot. Seed them early.

-allies. Giving a character friends or associates is a handy way of adjusting the tension band. The obvious is that an extra person or extra skills sway increase the likelihood for success– Joe picks up his friend Tasha who has no common sense but makes up for it in martial arts skills. Or Tasha might be clumsy but brilliant, or know how to hack security systems at the local secret government research facility.

Allies can also be detrimental. Giving Joe—or any other protagonist—a moral quandary involving a friend/lover/associate can create new layers of tension. Does Joe sacrifice Tasha to save himself in the climactic moment? Adding interpersonal tension reduces the need for greater external tension. It’s easy to be snuck up on when you’re distracted.

-weather/terrain. Your character can’t control everything. Rain, darkness, middle of the mountains—essentially out of their comfort zone—is going to give them a disadvantage. Taking some of the earned power away, temporarily, should feel like a hurdle and not a convenience to the writer. Joe.2 uses his lack of smell to crawl though the dark and unfamiliar sewer system hoping that zombism isn’t carried by rats

-All of this, but for the antagonist. Make sure that your antagonist is progressing at a reasonable rate for their character. It makes sense that they would also be growing, learning, training, recruiting minions. That zombie horde running through Joe’s town is recruiting members too.

All of this can really be boiled down to “keep things balanced”. Characters should be a healthy mix of capable and flawed, the natural world should be chaotic neutral, and in the end it doesn’t matter who wins as long as the resolution feels satisfying. Maybe Capable Joe gets over his fear of death and goes down swinging his wrench to give Tasha enough time to get into the control room and release the toxic anti-zombie gas. Or Joe.2 wields his sword from the passenger window while Tasha drives the rusty van like a battering ram to the edge of town which collapses in the huge sinkhole Joe created by sabotaging the sewers.

Narrative tension is a tricky gal. Staying within Schrödinger’s Tension Band keeps things feeling plausible while still exciting and suspenseful, which keeps the readers turning pages long after the bathwater goes cold.

Leave a comment