Last March I led a workshop titled “Uncovering Historical Characters and Making Them Your Own”; it was a 101 on character building using real historical people/archetypes as a template. I included some information on where to start with research, but it wasn’t the primary focus of the class. I was therefore quite surprised when research came up over and over in the question and answer time.

“Where do you start?”: This is usually the first question people ask when they find out I write Historical Fiction. My short answer is “something that you are fascinated by.”

Depending on the length of your work, you could spend years researching and writing in a specific period or on a narrow topic; the more interesting you find it, the easier it is to put in the hours. I love American history—specifically women’s experiences—and have had a delightful time mining the archives for unique glimpses that I can translate into narrative.

Another place to start is find a historical person or type of person (Calamity Jane/Cowgirl) and base your story off of their experiences, or put them in a made up place that is historically accurate*. I prefer to use real people from history as characters because I have a great excuse to search through primary source documents, newspapers, and other sources to build my work. It adds an extra challenge to the process.

Maybe you have a scenario in mind: guy gets lost in the woods. You may need to try different time periods or settings to find the right fit. Choosing a location of which you have some prior knowledge is helpful, but not required. It just depends on how much research you are prepared to do.

Finally, sometimes you may have a great idea that leaps into your mind fully formed. I have dreamed a couple of my short stories, woken up and written them down.

“Now I have my idea; where do I go for research?”

Not going to lie here, I often start with wikipedia. Back in my student-teaching days we told kids not to use wikipedia as a citation; today I glance over the article I am reading and head straight for the blue links at the bottom of the page.

Ancestry is another great resource, especially if your local library has a free version to log onto with your card number. Because Ancestry is crowd sourced, I take their tree suggestions with a grain of salt until I see primary source documentation to back up relationships, but that same crowd sourcing means that the linked resources to individuals can be massive. Let other people do work for you!

Just a note, a lot of people have the same names; sometimes in the oldy times a kid would die and the parents would name the next kid to come along the same name. I have a several generations ago relative who lost his first wife then married someone with the same name who was then quoted in history books for the first wife’s accomplishments. A quick check of dates can uncover a lot of misrepresentation: Grandma Ann may have had twelve children but if the Ancestry tree is claiming four were born after she was sixty…

Podcasts are my next go-to for information. Even before books! There is a wealth of podcast information on just about anything you can imagine. I try and find channels sponsored by academic institutions or reliable networks, but occasionally Joe Schmoe takes it upon himself to detail every Napoleonic battle in great detail and I am there for it. I also find it helpful to listen to author interviews on books I am considering adding to my library. Frequently I get what I need in that hour talk vs. reading the entire work.

Books. I have a large collection of research books (living in a retirement community with a great Friends of the Library book sale each month helps). While my compendiums, encyclopedias of various topics, and old textbooks on historical costuming and abnormal psychology are well thumbed, many of my books sit for years until I need their niche information.

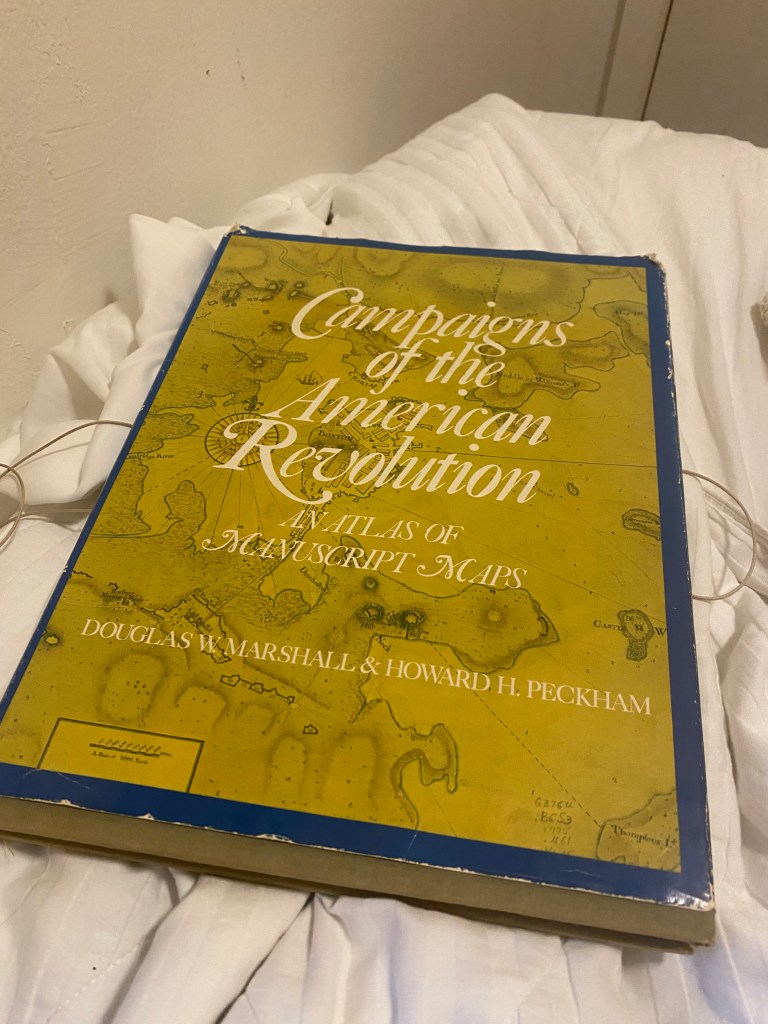

At the moment I am using Campaigns of the American Revolution: An Atlas of Manuscript Maps by Douglas W. Marshall &Howard H. Peckham to begin outlining my next novel. Like many of my most useful starter books, it covers a single topic broadly—in this case the various campaigns of the revolution in chronological order, by region, succinctly. Because I am still discovering my plot, Campaigns gives enough direction to let me weed out setting possibilities, play with character options, and see the causes and effects on a large scale to see if they meet my plot needs. Once I have a better idea of my plot and characters I will hit those niche books (Like my copy of George Washington’s campaign ledger) to look for nuggets to flavor my story.

“How much research is too much?”

This is highly subjective and depends on a few factors.

How “real” is your story? Whatever the answer to that question, you want your readers to stay immersed in the narrative. If there are anachronisms or oddities, they will pull readers focus. While not everyone is going to question why your 19th century Irish character is named Oliver, they likely will ask why there is a French Bakery in your 17th century Old West mining town…as well as why there is a mining town in the Old West before there was an Old West.

Is this a plot based story or a character based story. If your characters are on the page to show the action (The Alamo, Waterloo, The White Chapel Murders) then you will be doing a lot of in-depth research on the events and setting you are writing. It is unlikely that you will be needing copious details about the kind of tea kettles the character is using on the campaign, or how their socks feel when wet.

If the plot of your story is a vehicle for a complex character arc (Think B plot in a movie) then you are likely going to be largely writing about the Character’s interactions with other characters in the historical setting. This is where small details like clothing, daily tasks, job specific details etc. become essential. This is a different type of research that often sends me to peer reviewed journals or museum photo galleries.

Regardless of which element is forward in your story, your narrative can get bogged down by details. I know I tend to info dump into my first drafts because I have worked so hard to find the details, I want a payoff! When I first started doing historical research I wanted to know everything. Now I want to know enough to sketch out some possible plot lines, enough “real” characters and setting details to flavor the story. The rest I work out as I write. Even into my second or third drafts you can find (fill in place) or (Costume detail) because the info isn’t that relevant to the narrative and I don’t want to stop my flow to google.

Research can by just as fun as writing, but it can also be a procrastination tool.

“How do I research traditionally otherized groups, or those whose history is difficult to find?”

This was one of my biggest questions when I started writing. As a largely non-marginalized person I want to write a variety of characters with whom I don’t share experiences. Representation matters and I don’t want to contribute to stereotypes or harmful narratives. Yet many of my characters are part of groups that haven’t left much historical records either because they were not an acknowledged population, or their history wasn’t valued. So where do I find these histories?

-Legal records. Many traditionally otherized groups had laws passed against their behaviors, professions, or relationships. Legal records hold a trove of historical details of Queer folk, middle class and impoverished women who behaved outside of social norms, and those within BIPOC communities.

-Ethnographies, biographies, modern non-fiction books written by people within the communities you are writing about. Reading descriptions about communities by members of the same is a great education. I don’t do this to appropriate the information, but to see first hand how people are describing themselves and their own history.

-Archives. Especially in the case of women’s history, archives are filled with unpublished resources. For hundreds of years collections have contained diaries, letters, common books, etc. that has been passed over for research because it was considered unimportant. Thankfully this is changing and more is accessible online, but visit an archive and look through the collection lists and you will almost always find something useful to your research.

-Historical Fiction written by members of the community. Again, this is not to appropriate, but to learn. Reading about a group that was written by someone writing what they know is invaluable. I personally shy away from writing flaws for fear of coming across as villainizing or stereotyping; reading well rounded characters is a reminder that whatever the factor that has caused a character to be marginalized may be it does not affect their ability to be wholly human, which includes flaws.

There you have it, Research 101. To get you started, here is a writing prompt:

Find someone in your family tree that did something exciting, write the event through their eyes.

OR

Find someone in your family tree that lived through an exciting time, write an interaction with another character while the two perform an activity of daily life.

*Historical fiction doesn’t have to be based on true events, real people or places. However! If the events, characters, or places aren’t historically accurate you move into Speculative Historical Fiction territory. Labeling is only important when you go to market your work.

Leave a comment